Yes, surge protective devices do wear out. Even when there is no visible damage and the device still appears powered, its protective components degrade with every surge event. Replacement timing is therefore not based on calendar age alone. It depends on cumulative electrical stress, exposure conditions, and system criticality. Assuming protection remains intact without verification is a common and costly risk.

Why Surge Protective Devices Degrade Over Time

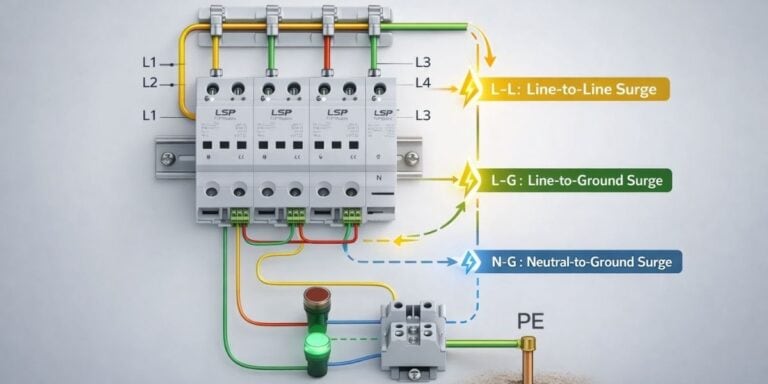

A surge protective device is a sacrificial protection element by design. Its internal components are engineered to divert or clamp transient overvoltage energy away from downstream equipment. This protective action is not unlimited.

The most common limiting components are metal oxide varistors and similar nonlinear elements. Each time they absorb surge energy, microscopic changes occur within the material structure. These changes increase leakage current, shift clamping characteristics, and raise internal temperature during normal operation. The degradation is incremental, not binary.

Cumulative exposure matters more than a single event. Routine switching transients from motors, variable frequency drives, contactors, and utility grid operations occur far more frequently than lightning-related surges. While individual switching transients carry less energy, their repetition contributes significantly to long-term wear.

Thermal stress accelerates degradation. Elevated ambient temperatures, insufficient ventilation, and sustained overvoltage conditions all reduce component life. Importantly, a device can remain energized and show normal line voltage while its protective path has partially or fully failed.

This is why “still powered” does not mean “still protective.” Electrical continuity and surge diversion capability are not the same function.

Common Signs an SPD May Need Replacement

Some surge protection devices provide indicators to signal loss of protection, but these indicators have limits. Common signs include:

- Status indicator lights

Typically show whether one or more protection modes remain connected. They do not measure remaining surge capacity. - Audible alarms

Present on some panel-mounted devices. These usually activate only after a complete mode failure, not during gradual degradation. - Loss of protection mode

A device may continue operating with reduced phase or mode coverage, leaving part of the system unprotected. - Thermal disconnect activation

Indicates severe internal degradation, often after the protective components have already been stressed beyond design limits. - Silent degradation

The most dangerous condition. Protective elements may be weakened but not fully disconnected, providing a false sense of security.

Many degraded devices show no external symptoms at all. Relying solely on indicators is insufficient for risk-based systems.

Why Visual Inspection Alone Is Not Reliable

Unlike fuses or circuit breakers, a surge protective device does not fail in a clean, mechanical way. Breakers open under defined conditions. Fuses melt when current exceeds a threshold. SPDs fail electrically long before any visible damage appears.

Internal varistors may crack, partially short, or increase leakage while remaining physically intact. Encapsulation hides these changes. There may be no discoloration, odor, or deformation.

Indicator circuits monitor continuity, not performance. A protection element can remain connected while its clamping voltage has drifted upward beyond acceptable limits. In that state, the SPD is technically “on” but functionally ineffective.

This behavior is fundamentally different from overcurrent protection devices, and treating SPDs as visually inspectable components leads to under-protected systems.

Expected Service Life of a Surge Protective Device

There is no universal service life expressed in years. Any fixed replacement interval that ignores exposure conditions is misleading.

Service life is influenced by:

- Surge frequency

Facilities with frequent switching events experience faster degradation. - Surge magnitude

Higher energy events consume more protective capacity per occurrence. - Installation location

Devices installed closer to service entrances encounter higher surge energy than downstream units. - System grounding quality

Poor grounding increases stress on protective components and reduces effective diversion. - Operating environment

Temperature, humidity, and enclosure conditions affect thermal aging.

In low-stress environments, a surge protection device may remain effective for many years. In high-exposure installations, degradation can reach unacceptable levels much sooner. Replacement should therefore be condition- and risk-based, not age-based alone.

Replacement Considerations by SPD Application

1) Electrical Distribution Panels

Panel-mounted protection devices are exposed to a broad range of transient sources. Utility switching, internal load changes, and upstream faults all contribute to cumulative stress.

Because these devices serve as primary protection for multiple downstream circuits, degradation has system-wide consequences. Even partial loss of protection increases the probability of equipment damage elsewhere in the installation. Planned replacement is typically more defensible here than waiting for indicator failure.

2) Solar PV Systems

DC-side protection is exposed to long conductor runs, outdoor conditions, and frequent environmental transients. Inverter switching and grid interaction further increase stress.

Degradation may occur asymmetrically across poles or strings. A surge protective device used in this context may remain electrically connected while offering uneven protection. Replacement intervals should account for environmental exposure and system downtime impact, not just device status.

3) EV Charging Systems

Charging infrastructure combines high-power electronics with frequent connection and disconnection events. Grid disturbances and load transitions are common.

Because chargers are often installed in public or semi-public locations, failures carry operational and safety implications. Waiting for complete protection loss before replacement increases the likelihood of charger damage and service interruption.

4) Control Panels and Sensitive Electronics

Low-energy surge protection devices installed near sensitive equipment are often the last line of defense. Their effectiveness depends heavily on upstream coordination.

These devices can fail quickly if upstream protection is absent or degraded. Replacement decisions should be conservative, especially where downtime or data loss has high consequences.

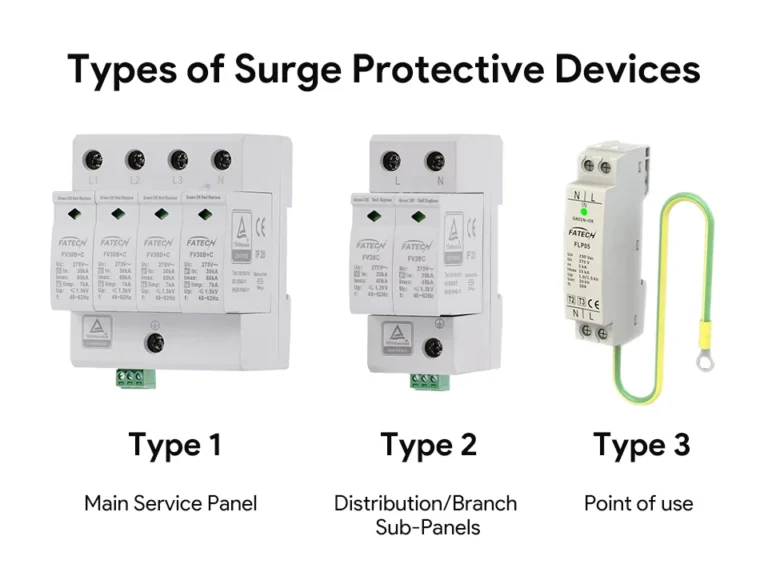

Type-Based Replacement Considerations

Type 2 surge protective device

These devices are typically installed at distribution levels and are exposed to repeated transient events. Degradation is gradual and cumulative.

Because failure is often silent until protection modes disconnect, relying on indicators alone is risky. Replacement planning should consider exposure history and system importance.

Surge protection device type 3

These devices depend entirely on upstream protection to limit incoming energy. When misapplied or used without coordination, they experience accelerated degradation.

They are more sensitive to upstream SPD health. If upstream devices have aged, downstream units may fail much faster than expected.

Maintenance, Monitoring, and Replacement Strategy

A structured approach reduces uncertainty and avoids reactive replacement.

Periodic inspection should verify indicator status, wiring integrity, and enclosure condition, but inspection alone is insufficient.

Status monitoring, where available, provides earlier awareness of protection mode loss. However, it still does not quantify remaining capacity.

Planned replacement based on exposure, environment, and system criticality reduces downstream risk. Replacing a degraded surge protective device is far less disruptive than repairing damaged equipment.

Failure-based replacement increases risk. By the time a device signals total loss, it has already ceased to provide meaningful protection, often for an unknown duration.

From a risk-management perspective, SPDs should be treated as consumable components with a defined role in system reliability.

Comparison Table

| Factor | What It Indicates | Replacement Implication |

| Indicator status | Protection mode health | Loss requires immediate action |

| Surge exposure | Cumulative electrical stress | Higher exposure shortens service life |

| Installation location | Energy severity | Upstream devices age faster |

| Grounding quality | Stress distribution efficiency | Poor grounding accelerates degradation |

| System criticality | Risk tolerance | Critical systems justify earlier replacement |

Common Misunderstandings About SPD Replacement

“It’s still powered, so it’s fine.”

Power presence does not confirm surge diversion capability.

“It survived lightning once.”

Survival does not imply no damage. High-energy events consume protective margin.

“Higher ratings mean it never wears out.”

Higher capacity delays degradation but does not eliminate it.

“No alarm means no problem.”

Many degraded devices provide no warning until protection is already compromised.

Conclusion

Surge protective devices are not permanent infrastructure. They are consumable protection components designed to absorb electrical stress over time. Degradation is inevitable and often invisible.

Replacement is not an admission of failure. It is a deliberate risk-management decision that protects connected systems, minimizes downtime, and preserves equipment integrity. The objective is not to maximize device life, but to ensure protection remains effective when it is needed.

FAQs

They do not expire by date, but they degrade based on cumulative exposure and operating conditions.

Indicator lights confirm connectivity, not remaining protection capacity. Exposure history and system monitoring are equally important.

High-energy events justify inspection and often replacement, especially for upstream devices.

They can be, particularly if upstream protection is absent or degraded.

Yes. Silent degradation is common and represents the highest risk scenario.